*Originally published 11/2022

Readers: Please spread the word about my Substack and consider A. Subscribing (free or paid); B. Recommending my Substack on yours; C. Sharing my Substack on your social media, on Substack, or anywhere else!

Thank you so much for being supportive and reading!

##

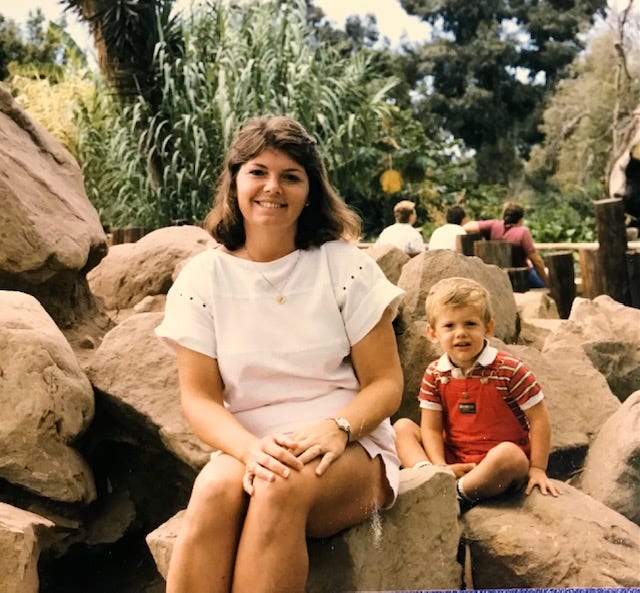

A Note about My Mother

I’m a mamma’s boy. I won’t even try to pretend. Yet it’s a fractured, tense history between my mother and me. My girlfriend has interacted with my folks several times now. She asked me why I still have such intense and often negative feelings towards my mother. As is the case with nearly all narcissistic people, my mother is a charming human being. Especially to people who aren’t me. And even more so with women I’m dating. (Until recently it’s been a while in that department.)

I want to explain a few things. Because I truly, deeply love my mother. Always have, always will. But we do have a tragicomic past together, united by blood, DNA, family history, pain and trauma. More and more lately I’ve felt acutely ashamed when I cast judgment on my mom. It feels like I’m castigating her for no mortal reason; like I’m whipping someone who’s not only down but who’s been down for decades now. And yet it’s not for no reason. This being the case, the flip side is that my mom is and always has been a wonderful person and mother. Human beings are profoundly complex; our stories are usually layered, deep, nuanced, unexpected. My mom’s story is no different. I love her. I cherish her. She’s always been both my most sincere confidant and simultaneously my sharpest thorn.

##

My mom was born in Eureka in 1950. Northern California rain and coastal fog. Her father—my grandpa Bill who passed away in 2015 at age 90—was a logger. Soon he and his wife (my mom’s mom) fled to Southern California, with my mom’s older brother and older sister in tow. They landed in Pacific Palisades, a middleclass community near Highway One.

On the outside, everything looked good. Big house. Money. Picket white fence; two-car garage. Church on Sundays. Dad worked at a plastics company and traveled for work a lot. Mom read books voraciously and was a feminist and loved to debate the merits or lack thereof and the patriarchal hierarchy of the Catholic church. My grandparents were high school sweethearts and could not be more different: She was intelligent, beautiful, cunning; he was soft, insecure, kind, open, like a big teddy bear.

My mom’s mom—my grandmother who I only met a few times in my vague, distant, blurry childhood—was trapped as a young mother in her early thirties. She wanted life experience; adventure. Her simpleton husband was gone often, and she was bored in the sexist 1950s and early 1960s. A housewife she was not. Think more of Joan Didion circa 1965. Whip-smart, lash-mean when she wanted to be, manipulative, tough. She didn’t want to be a mother. She didn’t want to be a wife…to my grandfather.

My mom was the youngest. Her older sister got pregnant junior year of high school and fled to go live with the boy’s family in Argentina and have the baby. (They’d met at Santa Monica High School.) Two years younger was my mom’s older brother—my uncle Pete. (My hero when I was a wild rock-n-roll rebel and alcoholic.) Around age fourteen my uncle moved out and lived with a good friend of his not far away, and then hitchhiked up to San Francisco to “tune in and drop out,” as well as dodge the Vietnam War in Southeast Asia.

That left my mother. Just her and her parents. Back in those days (mid-1960s) the priests would knock on locals’ doors and introduce themselves. When the local church got a new young, attractive priest with bleach-blond hair and striking blue eyes, and he knocked on my grandmother’s door, that was it. They fell for each other quickly, in little conversations over tea and coffee, when hubby wasn’t around. But my mom was around. She heard and saw it all.

Things got shaky and finally exploded. One day my mom arrived home from high school and found her mother’s Dear John. She’d found someone else. She didn’t say who that someone was…but my mom knew it was the priest. After this, realizing his wife was serious and was in fact not coming home, my mom’s dad had a full-on nervous breakdown. Eventually my grandma contacted the two of them, claiming she’d been raped by a mysterious man she couldn’t quite explain. She was staying at a house rented by the priest. It was all very shadowy and strange, like The Doors’ music back then. Savage, brutal, umbilically connected to a vast voracious void.

Unable to pay bills and function, my mother started using her dad’s money to do so. Her dad stopped going to work. At one point he made my mom drive all the way up to San Francisco (she was not yet 16 and didn’t have a license nor know how to drive) to attempt to locate his wife because he remembered a good friend of hers up there. (This was before grandma contacted them.)

Grasping clearly that her mother didn’t love her, and that her mom was essentially starting a new life without her children, and that her whole family had crumbled beneath her feet, my mom tried to end her life. A jar of pills were her choice. This landed her in the ER with a tube down her throat. She was 15. It was 1965. From here she was sent to the psych ward. She saw several old male shrinks. She couldn’t or wouldn’t talk. Think the therapy scenes in Good Will hunting. Finally she tried to kill herself a second time, while in the ward, this time via her clothes as a rope.

As a result of this—and because she had “no family”—she ended up in the psych ward for two whole years. Can you imagine that? I can’t. While inside she grew up in many ways. She got her GED and applied to community college. She saw a therapist the whole time. She wept and screamed and became angry and even violent a few times. She established connections with adults for the first time; she learned what trust was; she grasped unconditional love. She read Man’s Search for Meaning which changed her life. She later wrote a book about all of this.

At 18 she became—ironically—a psych tech. She got married to a man she did not love. They had my half-sister in 1969. A couple years later they divorced. My mom had several more breakdowns in her late teens and early twenties. There were several more suicide attempts.

Then she met my father, who’d arrived in the hospital after a ten-day drinking binge which had culminated in cutting his wrists. He had come from a very different yet very similar background. A father who’d been detached and domineering, controlling and cruel. A mother who didn’t comprehend emotion. Formal higher education was all that mattered, above love or family or passion. My father felt unseen and unheard. And so he went off the rails.

They fell in love, of course, and moved in together—as I’m writing this I’m realizing I really should write a novel about their relationship—against their psychiatrists’ advice. They bought a house in Ventura, north of LA. My mom got pregnant again. My sister was 13 when I was born on the final day of 1982 and she shifted back and forth between her biological dad’s in LA and her mom and step-dad’s in Ventura. By age 5 my sister was off to UCLA.

As you can imagine, though my mother was much more stable when I was growing up than her mother had been, and more so than when my sister was a child, she was still far from perfect. No mother—no parent—ever is or can be perfect. I understand that to the core. The mistakes my mom made when I was young were largely driven by clinical depression, an inability to cope, deep, intense fears that she wasn’t good enough to be my mother or love me (because her mom had abandoned her so righteously and coldly), and a strong, fervent, unimpeachable desire to prove to herself (again and again and again) that she was not her own sordid mother.

She told me she loved me twenty times a day. She smothered me. She was inconsistent. The hardest thing was being dropped off once in the middle of the night at her psychiatrist’s house when my father was out of town on business and I was having nightmares and waking her up and she couldn’t cope and (she later told me) she was feeling suicidal. Then there was the kid up the street who placed his father’s loaded 9-millimeter handgun into my mouth (how he had access to it I do not know), backed me up against the wall, pulled the hammer back and told me to count down from 10, and “at zero” he’d “blow my brains out.” There was of course the molestation by my father’s work colleague’s 19-year-old son, down the hall in my own room while my parents ate dinner and discussed Bill Clinton, circa 1993.

There was the two-month psych ward stay my mom left for when I was around 12 or 13. There was the angry yelling between us. The hot, raging tears. My telling my mother of my molestation and her rebuttal that I had a “strong imagination.” There was that feeling of pure rage and an inability to trust adults which started inside me around age eight. There was the alcohol I discovered, finally some emotional medicine. There was the punk rock and the violence and the chaos, the rebellion and the danger and the blackouts and driving wasted every night for years. The nasty womanizing. The totalizing self-hatred. The desperation, the depression, the using my parents’ money. The neediness, the loneliness, the fear.

I felt alone, on an island. My father was an emotional wasteland. A desert mirage which slowly faded from reality when I approached it, thirsty and yearning. My older half-sister lived in LA; we were strangers. My uncle was cool and dark and still wild even in his fifties. I visited him in Venice Beach when I could. There wasn’t anyone else. Not in the family. We were small and fractured and cracked, like broken vases. My mother had always been concerned—obsessed—about the external world. Strangers. Neighbors. Random people. She never understood why I felt so distant and angry, why I left home at 19 without saying a word, simply throwing my stuff into boxes and loading my truck. She still doesn’t understand. And she still can’t see the pain I felt.

It's that harrowing lack of awareness which I think has always wounded me the deepest. She can find joy in the basic, easy things, but she can’t face her son who’s been begging for her to see him for decades. I’m still begging.

But now I am almost 40. She is 72. My father is dying from terminal cancer. I live in the same town as them, Santa Barbara. I fled New York City to care for him with her. Last year I lived with them for three months until I found an apartment. My mom and I had some explosive, intense, ruthless screaming fights last year. But for the most part since then we’ve been okay. We see things in life from radically different perspectives. She sees “dignity” in terms of how people on the outside perceive her. I see dignity as coming from within. Self-respect (speaking of Joan Didion: read her excellent essay on this topic) and self-acceptance and self-love, to me, is where “dignity” comes from.

In 2010—when I was 27—I hit bottom and got sober. I started doing AA. I got a therapist. I discovered Buddhist meditation. My life started to change radically. Working the 12-steps felt bizarre, fantastic and heroic, not to mention vulnerable as hell. I learned, slowly, to forgive myself. Eventually I forgave my mother. My dad, too.

The truth is there are a lot of good memories connected to my mother as well. Her warm hazel eyes and bright smile when I was a child. Hiking up to The Two Trees in Ventura with her, my small hand clutching her palm. Being read classic literature by her at night when I was eight, nine, ten. Our solo trips just me and her overnight to Solvang, where we’d hold hands and stroll along the shops and cafes and restaurants. Our chocolate Labs and her pugs. Her support of my surfing obsession when I was a teen; how she’d film my best friends and my waves constantly, grinning, the genuinely proud mother. All the times I got sick and had to stay home from school. She’d been a nurse and then nursing teacher so I always knew I was in good hands.

Her telling me, when I asked what the rules of writing were (around age nine or 10, when I was just starting to write poetry) that there WERE no rules, that you could “do anything.” (This is largely why I became a writer.) The deep, authentic, honest conversations we had (usually half-drunk on red wine) throughout much of my twenties, until I got sober. Her sending me black-n-white photos of she and her girlfriends partying with The Rolling Stones in LA in 1964. That night she gave me her entire vinyl record collection and my best friend and I discovered Bob Dylan and The Doors—“punk before punk.” The trips to Baja we took, those long drives from Ventura. All the support my mother gave me—emotional, financial, symbolic—even in the midst of my worst alcoholic insanity. She never gave up on me. All the editing she did on my first novel, and on many of my published stories. All the feedback and literary discussions. Her writing insight has always been beyond helpful. Her great big true love. Unconditional, even when I felt otherwise. Even when I felt I didn’t know who she was. Or who I was.

My point is: My mom is a good person. So am I. I love my mom more than anything in the world. She’s my best friend in many ways. When she dies my life will feel cracked open completely. And yet she also has left this vast, gaping hole in my heart which may never fully heal. Maybe it will. I honestly don’t know. I have let go of the past. Maybe I still tell people how “awful” my childhood was because I never got that apology I thought I needed; I never was, strictly speaking, “seen and heard.” But neither was my mom by her parents. My dad with his, either. And so it goes, as Vonnegut used to write.

I have tried as I’ve gotten older to soften. And in many ways I have. I try to see my mother as she is: Intelligent, kind, deep, thoughtful, and yet also narcissistic, self-absorbed, in denial, unself-aware. Perhaps these are the necessary psychological defense mechanisms of a survivor, which my mom most certainly is. As I am. As my uncle is. And my father. And my sister. My whole family. This is familial trauma. The cycle. Genetics. Nature and also nurture. The diamond and the knife.

Life is short. My grandparents are all dead and gone. Dad is not far from the grave. My mom? Who knows. Myself? I am alive right now. I grew up spoiled and privileged and loved and very lucky. And I grew up with bittersweet darkness, feeling imprisoned in the depths of my mother’s tainted soul. Can both exist at the same time? I say yes. They can. This is the human condition, the human experience, the human nature of suffering and love.

My mother is not perfect. Nor am I. I see my own narcissism. I know where it stems from. I see my intelligence and creativity, too. I know where that comes from as well. We take these things inside, the good and the bad and the lovely and the ugly. Because that’s what life is. All of it.

The dirt and the mud and the grass; rebirth. The cycle.

Because of my mother, I nearly ended my life.

Because of my mother, I survived.

##